Where We Dance

From closures and gentrification to post-COVID alternatives, Jim Ottewill’s new book Out Of Space looks at the shifting nature of nightclubs across the UK. We hit him up to ask what he’s learned through his extensive floor-focused research.

The narrative around the pressure on Britain’s club landscape has been bleak for some time. When property developers operate with impunity and dance music’s cultural cache is viewed dimly by authorities, there’s little in place to protect these bastions of expression, enjoyment and escapism. We don’t need to tell you about how frequent club closures are – the list of iconic spaces falling prey to gentrification and urban planning is too long to bear – but it’s also important to note the adaptability and resourcefulness of underground and independent culture. It’s never easy operating a venue even in more conventional terms, let alone the clandestine and fringe endeavours often required to pull off loud parties until late hours in our increasingly claustrophobic towns and cities, but the impetus to dance is not easily stamped out, whatever the climate.

It’s a unique era for dance music culture overall – a culture old enough now to have first wavers in positions of authority who might well have found themselves at a free party in Blackburn or the Peak District in the 90s. Britain will quite happily trade on the globally recognised mainstream face of dance music as part of its identity now, but there’s always a thread of denial about the reality of this culture, not least its fringe aspects in the present day. But even if it’s bedded into the national fabric, it’s also in a state of flux as generational shifts and the virtual realm change the way young people engage with dance music.

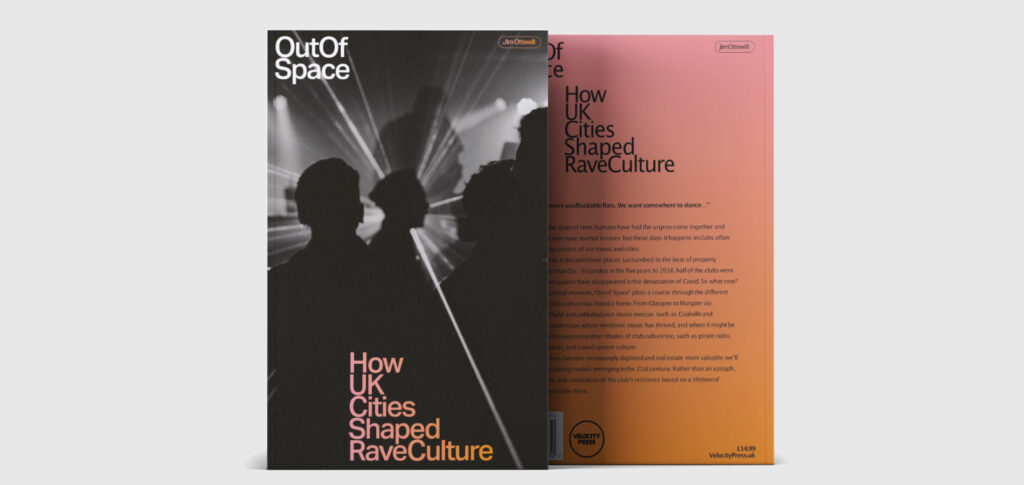

UK music journalist Jim Ottewill has taken this backdrop as the jump-off point for his new book, Out Of Space – How UK Cities Shaped Rave Culture. It’s coming out via Velocity Press – a relatively young publisher doing a great service in documenting different aspects of electronic music culture. Ahead of the book’s publication on July 8, we wanted to ask Ottewill about what he’s found out on his missions across all manner of club spaces.

What motivated you to write this book in particular?

While living in London, I wrote a piece for Mixmag in 2017 about the plight of the Joiners Arms, this LGBTQ+ venue and institution on Hackney Road in between Bethnal Green and Shoreditch. It was somewhere a lot of my mates would hang out, was suitably down at heel and pretty chaotic for a night out. Back in 2014, it suddenly came under threat from property developers – and this was around the time Fabric was under a lot of pressure due to the tragic deaths that occurred under its roof. There were all these shocking stats being thrown around about how many LGTBQ+ venues had been lost and it suddenly felt like we were at this watershed moment for nightlife in the capital. Fabric survived and the wheels kept turning until COVID shut everything down…

Then when I left London around 2019, I spent time in Sheffield, Scotland and eventually ended up in Liverpool. Through going out in these places and experiencing life outside of Hackney/Dalston, it seemed like this story of city centres gradually becoming hostile towards clubs was being repeated and not just unique to London. I was interested to find out how different cities had impacted the ebb and flow of club culture, the prevalence of this trend for clubs being pushed to the edges, how these places have shaped electronic music (whether that be in terms of sound, scene or some other defining factor) – and perhaps most importantly, what the future for club culture looks like in this context.

Were there particular patterns or trends you noticed when you started to dig into research across the country about the state of nightclubs / club culture?

The story we’re all familiar with is one of nightlife locked in this grim downward spiral. And during the decade or so I spent living in London from 2007/2008, it definitely felt you were constantly reading about the demise of yet another amazing music venue, whether it be a club or live music joint. From great spaces like Plastic People to The Cause, this narrative of loss can’t be ignored – and it’s been driven by a variety of factors, from the unstoppable march of property development across the capital, unwieldy licensing regulations to the killer blow of COVID and all the associated restrictions, as well as the way in which entertainment tastes are evolving.

Yet, ‘loss’ is only one strand of what is a pretty lurid and rich tale of late nights, ace music and amazing parties. Instead, what has been perhaps most striking is the ingenuity of nightlife to survive and sometimes thrive, no matter how adverse and shitty the conditions. From raves in abandoned mills to embracing virtual environments and temporary states (like Despacio which is defined by its transience), club culture is a fluid, restless beast. It often gets a kicking from someone or something but it has this incredible ability to pick itself up, dust itself down and move forward, by embracing technology, new spaces and other opportunities – it’s all the more exciting for it.

How would you describe the role of provincial clubs compared to venues in bigger towns and cities?

Obviously, a much told pillar of dance music’s year zero story is how certain London DJs went to Ibiza, discovered ecstasy and Balearic music, brought it back to the UK and wham – acid house. While this is definitely part of the story, there are myriad other narratives behind its rise. It was particularly eye-opening to speak with various DJs and promoters about the importance of the network of clubs in places like Derby, Nottingham, Milton Keynes, Coventry and Coalville (whose geographical location was really important in it becoming a port of call on a night of DJing). There are other clubs which I didn’t include, but places like the Orbit in Morley outside Leeds had such killer line ups too, Renaissance in Mansfield as well. Mick Wilson is an editor at DJ Mag and was a resident at the Eclipse in Coventry when house music took off and in an interview he describes these provincial towns as ‘super-feeders’ in getting the club scene going.

If you look at today’s club culture, then this trend persists – in many of the towns around the South Coast in places like Margate and Hastings. Bill Brewster told me that a gig at the Marina Fountain in St Leonard’s was one of his favourites and it’s somewhere beloved of Ashley Beedle and the We Are the Sunset crew. In Margate, there’s a scene flourishing, full of dance music heads like Hannah Holland, Matt Walsh and Ghost Culture who’ve ditched London in favour of more space, cheaper rent/mortgages and sea air. Are big cities important? Undoubtedly. But these smaller scenes are just as vital in giving a space for alternative, more experimental styles, tastes and persuasions a chance to grow.

Out Of Space – How UK Cities Shaped Rave Culture by Jim Ottewill is out July 8 via Velocity Press. There will be a launch event for the release on July 14 at Rubadub in Glasgow, with Ottewill chatting to Sub Club’s Mike Grieve, Monox’s Dan Lurinsky, Mairi MacKenzie and Sondhaus’ Lynn Macdonald. You can find more details here.