Space Afrika // Live at Kings Place, London

Joseph Francis reflects on the most recent work of Space Afrika – their 2021 album Honest Labour and a compelling live show at Kings Place in November.

Living in a city, you’re never too far away from the sound of a pneumatic drill or the clank of scaffolding. If the adjective ‘ambient’ literally means “relating to your immediate surroundings” then the persistent idea of ambient music as soothing background noise is a way off the mark. Huerco S, who was lauded as one of the best ambient producers of 2017, even cringed at the thought of his music being so non-intrusive that it essentially becomes, “productivity music, capitalist music.” Recently, however, projects such as Space Afrika have turned ambient from an object of passive listening into a genre that demands active participation from its listeners.

In the past, Joshua Terelle and Joshua Inyang’s work as Space Afrika explored the outer edges of techno and house, infusing them with dubbed-out atmospherics. It wasn’t until the tragedy of George Floyd’s death that the two made a drastic change in their style, deciding to bring a more socio-political edge to their sound. Dissecting the beatless aspects from their Somewhere Decent To Live LP and marrying them with found sounds, the two curated a series of ambient shows for NTS radio which were then whittled down into a 30-minute album hybtwibt? (have you been through what I’ve been through?). The album collates vignettes of protests, interviews and speeches alongside tape effects, soul samples and hazy synths to produce a tapestry of heartache.

In an interview for Crack Magazine (around the release of their third album Honest Labour), Terelle said, “What we do is inner city ambient for chaotic living.” The chaos of which he speaks is twofold, representing both the common day-to-day hustle of a city (commuting, crowded spaces, constant construction) and the brushed-under-the-carpet chaos of those living in desperate conditions, trying to make ends meet. As a result, moments of peace are only fleeting within Honest Labour: Guest’s serene vocals on ‘Rings’ are jarringly interrupted by blasts of static, Blackhaine’s frank lyricism cuts through the melancholic strings and lo-fi drums on ‘B£E’ and ominous guitar chords creep alongside Bianca Scouts’ ethereal singing on ‘Girl Scout’.

But as hybtwibt? had alluded to, I haven’t been through what Space Afrika have been through and there’s only so much that an (albeit disruptive) ambient album is going to show me. It seems Space Afrika are aware of this so, across four acts at Kings Place in London, they joined together with fellow Mancunian talents, poet Isaiah Hull and photographer, filmmaker and poet Tibyan Mahawah Sanoh, to broaden the scope of their recent projects.

Opening with a distant, nighttime shot of Manchester’s Arndale centre (one of the UK’s largest shopping malls) we were immediately thrust into the brutalist landscapes from which they draw their inspiration. With the way the building frequently resurfaced throughout the set, by the end, I came to see it as a soulless, omnipresent monolith. The close-up shots that made up most of the collage were modest and less imposing in comparison, moving from highways to puddles, from cars to bikes, from panoramas to underpasses. Interspersed amongst the relative calm were moments of dissonance which echoed the aesthetic of Honest Labour and challenged the viewer’s perspectives.

One such moment came via headcam footage of a motorcyclist. Thanks to the subtitles beneath, my initial feeling was one of danger: the motorcyclist was either being chased or chasing someone. Along with the rest of the sequence, it was part of a loop which gave the audience another opportunity for reflection and a renewed perspective. When this clip came around again, it played beside the words from Honest Labour’s ‘Preparing the Perfect Response’: “I may not be the nicest person but I have a good heart.” This inclusion offered a new outlook, diffusing my initial paranoia and replacing it with empathy.

Following a short break, collaborator Tibyan Mahawah Sanoh appeared next to perform her poetry, adding a theatrical layer to the evening. To the right of the stage and under a spotlight stood a collection of framed family photos. On the left sat Mahawah Sanoh, who spoke of injustice and a lost youth accompanied by eerie, elongated strings. “Two hands clapping for someone’s truth / Queen of the pigs sat at that courthouse / Just snort it’s all rigged / With no hands clapping for no shitty youth.” Later, Mahawah Sanoh knelt on the floor behind the family photos and repeated, trance-like, “Is it dad’s fault? No.” Between her poems were interviews (perhaps recorded by herself) which described racist attacks on Black people, shocking not only in their content but in how recently they had happened. She ended her performance with a recording of some boys discussing the hostile and run-down appearance of a certain council estate. They spoke critically, sounding as though it wasn’t the same environment they had come from themselves, but it was ambiguous. Mahawah Sanoh’s words — “It’s all rigged” — lingered in my head afterwards, leading me to question whether the boys would find an alternative to what was in front of them.

Afterwards, Space Afrika and Mahawah Sanoh left us alone to watch their collaborative short film Untitled (To Describe You) for the evening’s penultimate act. Commissioned as part of the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival back in November 2020, the film took us through similar urban settings as the rest of the evening but with occasional bouts of intimacy, narrowing in on humans and perhaps the more physical, bodily relationships we harbour within these urban confines. For the most part it was a sombre affair, with some graphic images alluding to knife crime and both mental and physical health. Towards the end, light relief came by way of a romantic couple, smiling and laughing, on the set of a homemade photoshoot. In this context, the film felt like an interval; a space for us to catch our breath and reflect in between the two live performances.

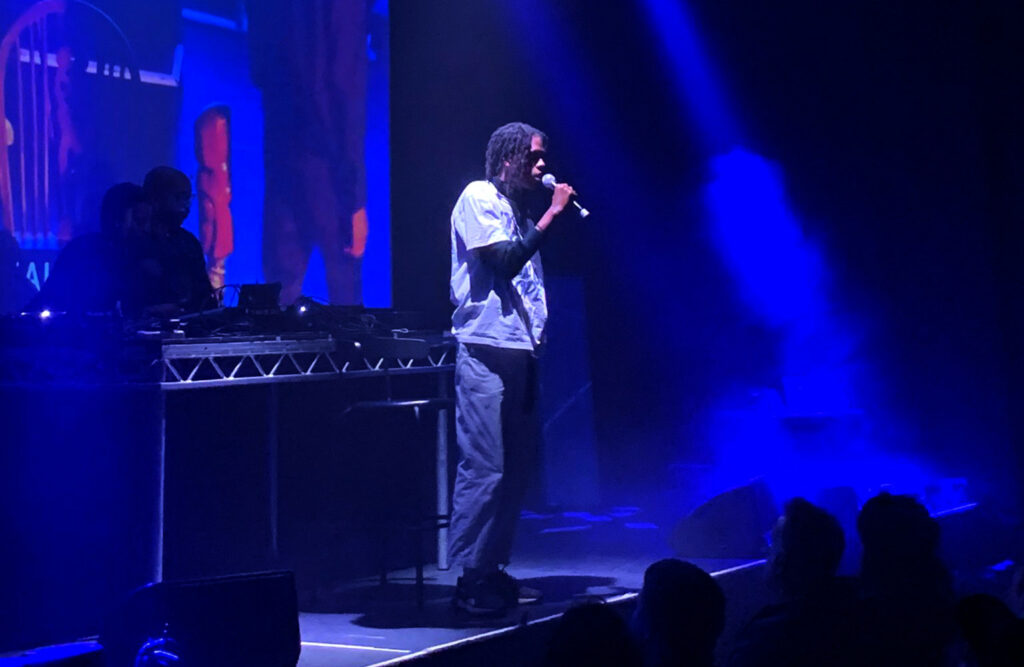

For the final act, Isaiah Hull took to the stage to deliver his resonant, often confrontational, poetry. Wearing a t-shirt that read “I hate famous people”, Hull immediately delved into a plodding rap accompanied by a catchy combination of strings, baritone vocals and treacling rewinds. Gradually, the apathy in his voice turned desperate as he spoke of not fitting in, “You don’t like the taste of the way I live / if life’s a game, I must be a glitch.” Above all, his lyrics celebrated the Black image and the exclusivity of his own experience. “Cruel Britannia / Cruel Britannia,” he repeated, “My skin is djembe / my hair is legba.” The references to djembe and legba are unfamiliar to me: both are rooted in West African and Caribbean tradition and folklore. In light of Space Afrika’s visuals throughout the evening, perhaps Hull was exulting in a vibrant culture which has been suppressed by poverty and institutionalised racism here in Britain. The following line drove the point home, when he said, “We were rich and rural.” At no point in the evening was there evidence of anything rich and rural: the clips were monochrome and the landscapes often sharp and bleak. It seemed Hull’s performance was making a distinction: whilst Space Afrika might be inviting us to share in an experience, let’s not forget the focus is on a Black experience.

I had arrived expecting to see a live performance of Honest Labour, with performances from the album’s collaborators. What I got was something far more holistic and varied. Context shapes meaning and this is what Space Afrika seem to be exploring to its fullest via the medium of collage. With repetition, careful curation and changes in perspective, Space Afrika shared a ‘news feed’ of experiences that was both patient and demanding of its audience. Although it wouldn’t be possible for me to leave feeling like I had fully grasped the depth of experiences shared, I felt as though I had been a part of something sincere and open. At times it shocked and shook me, at others it simply held up an image like a Rorschach test and asked, What do you see?

Photo credit: James Kinnaird.