Kelan: Stripped

Joseph Francis explores the physical, confrontational work of Max Kelan, a multifaceted maverick testing limits and exploring the human condition from the enclave of the Bristol underground.

Your body will bend around me and you will soon be sucking the filth off your feet

A voice flings forth the Fs from its bottom lip and salaciously draws out every S. The syllables linger in the abyss like the chime of a gong, alarming the listener with their resonance.

Don’t worry, you too will rise up from this shit again

Earlier this year, Bristol-based multidisciplinary artist Max Kelan released a cassette tape of poetry readings. Liberated from accompanying sound, his readings captured both the solace of a world locked in and an organic approach to sharing art. Despite emerging after the world had been forced into a state of reflection though, these poems have built up in his journals over years, forming the basis of his various projects.

“Salac, Bad Tracking and Kelan are all developed characters and they’re all from up here,” Kelan explains, pointing towards his head as he faces me over a video call, topless, from the garden of a shared flat, “Writing has helped me to learn a lot about myself. I think everyone should get their thoughts down on paper. It’s the best therapy.”

Summoning thoughts from the deepest recesses of his mind, Kelan confesses them candidly from the pulpit, ashamed of nothing. Throughout the readings, we are left with vivid images of intertwined bodies and earthly desires. Beneath it all lie messages of freedom over repression: “My freedom wriggles and writhes between every orifice,” he declares. “Never feel restricted by the limitations of your body. This body remembers nothing.”

Growing up in the rural Welsh town of Carmarthen, Kelan didn’t feel truly comfortable in his own skin. Only recently identifying as bisexual, he had never found anywhere he could openly discuss sexuality as a teen; the air was plagued with masculinity. “I’m a feminine man and I’m very camp, but there is definitely a laddy side to me,” he says. “I don’t like the fact that we live in this world where it’s one or the other. I’m interested in hundreds of things.”

Although his parents had allowed him to freely explore his alternative interests, including grindhouse and industrial music, it wasn’t until he began working at Carmarthen record store Tangled Parrot that he found a musical mentor. Store owner, Matt Davies, encouraged Kelan’s open-mindedness, introducing him to new bands and genres. Courtesy of Davies, a teenage Kelan, not yet old enough to order a pint, was soon DJing his newfound love of dubstep at clubs around Wales.

Off the back of DJing, Kelan met Gordon Apps and together they formed Bad Tracking, an industrial duo who would later be known for their highly controversial performances, challenging what many might envisage of an industrial/noise set. “[Noise music] brings to mind some guy who’s not left his room in years just sitting twisting some knobs and making some really horrible sounds,” he comments of the genre’s blinkered label. “We wanted to bring in some more performative elements, be theatrical and make it something that an audience could really engage with.”

To imagine a Bad Tracking show as simply ‘theatrical’ does not do it justice. In the past, Kelan has commanded audience members to spit on him as he prowls around on all fours, naked and slobbering through a ball gag. “The character I’m playing is supposed to be stripped down to nothing, totally giving themselves up to this technological world.” With our feverish dependence on dating apps, social networking and smartphone updates, their allegory isn’t far from the reality we live in.

However, with Bad Tracking, Kelan and Apps aimed to show rather than tell. “We wanted to leave these sort of aesthetics in front of people and then they can create their own narrative as to what it might be.” With this in mind, there was still room for Kelan to explore more vocal and blatant avenues of expression. On the pair’s Widower release for Bokeh Versions in 2019, words from Kelan breathed new life into their sound as he denounced our apathy towards this “world of unlimited leisure” through a maelstrom of piston chugs and electromagnetic distortion. It wasn’t long after this Kelan would also begin contributing his spoken word towards another project, Salac.

Equally interested in the pagan folklore of medieval and rural Britain as he is in current socio-political affairs, Kelan teamed up with vocalist and producer Cliona Ní Laoi to create haunted atmospheres combined with esoteric poetry. Kelan’s words are dispersed through a fog of memories, nightmares and ceremonies, intermingled with the incantations of Ní Laoi. On tracks like ‘Procession To The Underworld’, a sub swamps the hollow ripples of drums, while on ‘The Alter’ we’re left with screams as Kelan is “dragged down the fucking altar” like a lamb to the sacrificial plinth. Despite these engrossing, almost cinematic scores, Kelan’s words were entrenched in a quasi-fantastical realm, saturated with effects.

“In Salac and Bad Tracking, the lyrics are buried under so much noise. [Downtown] is the most straight, down-the-line thing I’ve done.” He’s referring to his debut solo album, due to be released by Bristol Normcore early next year.

Written whilst Kelan was living in a freezing cold flat in Berlin during the lockdown, the album oozes with angst. “At the time of writing, I was pretty upset and depressed. I’d gone through a break up, and the person I was living with was struggling mentally as well. I’d like to think [my feelings] really came out on the album.” In intervals between writing, Kelan would wander the streets of Berlin. During this strangely desolate time of lockdown, there was nothing to distract from usually clandestine acts, and no reason to hide them. Addicts would freely cook up heroin in plain sight as though the streets had become their own private space into which he was peering.

Downtown embodies the raw images and feelings from his time in Berlin both sonically and lyrically: Kelan lays bare his own inner turmoil and society’s gross injustices in a deliberately flagrant way. On ‘The Rag’, Kelan hocks up phlegm and spits it at the English flag as he shouts, “Crucified against the St George’s Cross, that’s how the colour of it turned red.” The song chastises the political right-wing for their use of nationalism to obtain positions of power. It’s an opinion and Kelan chooses to share it unapologetically, “I really don’t like that we’re living in this time where we’re tiptoeing around each other, making sure that we’re always saying the right thing and ticking the boxes to hit the safe, ‘nice’ criteria. I’m not saying we shouldn’t be looking out for one another, but people really need to stop policing each other and start having good conversations.”

Naturally, with his forthright approach, he has been met with opposition; people have found his performances as Bad Tracking offensive and accused him of arrogantly using his position as a white, cis male to tackle issues of body trauma which could be sensitive to someone who is transgender. As someone who lives with such traumas himself, Kelan wanted to meet for a conversation, but the people in question were not interested in what he had to say. This, he argues, is emblematic of an attitude that is currently pervading much of society and which he is eager to fight against since it squashes individual thought, “Cancel culture is the same mentality: ‘we’re shutting you down and you’re not allowed to say your point and you should be ashamed of all the things you’ve done.’”

Downtown celebrates individuality by creating stark contrasts between the real (it) and the formulaic (pop). At the start of every Downtown performance, Kelan opens with Petula Clark’s 1965 single of the same name. Its glossy, jaunty voice presents a perfect facade which has come to be likened with mainstream music. Once the song has finished, Kelan abruptly shatters its falsehood. “Everything is just a representation of something that’s already been represented, but that never represented me,” he cries out candidly through the silence before drums thunder amidst a seething haze, giving it an air of animosity.

“I wanted to make my own fucked up version of a pop album,” he explains, “Something that anyone can listen to.” By making both its sound and content accessible, Kelan created something that can rally everyone, including those who feel their thoughts are underrepresented.

Taking inspiration from songs like ‘Hey Mickey’ and ‘I Want Candy’, Kelan used simple structures as channels for this politicised take on pop. In fact, the album’s structure is so straight-forward it’s almost unconventionally conventional. “I enjoyed working with real limitations. It allowed me to get very creative with literally nothing, just my voice and this drum machine and a few pedals. [I enjoyed] having to structure songs in a different way [to how I usually do], like doing verse, chorus, verse, chorus. Although, I probably did it wrong, ” he smiles. Age-old pop formulas are put into overdrive so that both chorus and verse mesh into one, making it unclear where one starts and the other ends. Catchy anthems are crafted out of blatantly political and open lyrics — think football chant meets therapy session. Not to mention, Kelan’s voice is completely unedited causing it to occasionally waver along with his errant emotions: at times he is seductive (‘Factory of Sins’); at others weary (‘Pieces’); and others incensed (‘Towers of Future Guilt’).

Challenging perfectionism is at the heart of everything Kelan does. We humans are imperfect blobs of matter who haphazardly jostle through our daily lives, utterly incapable of reaching any so-called ideal. Therefore, rather than attempting to fall in line like the atoms of a solid, Kelan wishes to flow, liquid-like, along an ever-changing sewage of imperfection. “We are all disgusting. We all shit, we all spew, we all piss ourselves, and we all get drunk and do disgusting things. A lot of us are very disgusted with ourselves all the time, so why not fucking celebrate that?! I hate the fact that people think we’re living in this open, free time; it’s a load of bollocks. There are still so many rules.”

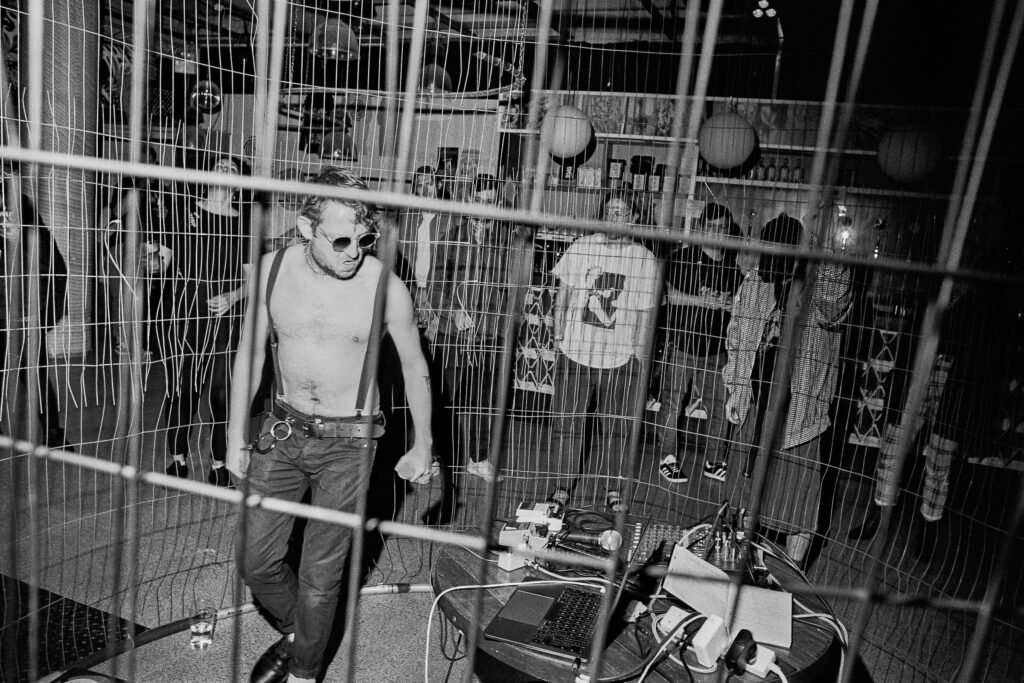

Recently, Kelan performed in a cage — a lifelong dream of his since seeing industrial band Ministry do the same. For someone who performs naked before a crowd, it was surprising to hear that he’d put up such a barrier between himself and his fans. He assures me that this made the performance no less physical; the audience shook the cage while he pushed back from inside. Yet, as I imagine this, I wonder who is really doing the cage-rattling here — us or him.

It seems through his various projects, Kelan has unburdened himself from the many layers that make up who he is, arriving now at Downtown, his barest expression yet. Through journeying inward, he is now the one who is free, and it is we who need our cages rattling.

//

Photo credits: Kelan portrait shot by Hamish Trevis. Live performance photos by Jodi Rogers.