DJ Bone’s Protest Music

The murder of George Floyd in May 2020 threw the issue of race inequality into sharp relief across huge swathes of society, especially in America. The grim reality of oppression, both blatant and subliminal, for Black people and other ethnic minorities in the Western world became foregrounded in that moment, but it has been a constant throughout history since colonial powers sought to exert supremacy over, and profit from, Black and Brown bodies no matter the human cost.

As people of all ethnicities started to face up to uncomfortable truths about societal inequalities, the electronic music scene had plenty to reflect on as a white, male dominated industry built upon Black creativity. In many ways that creativity was, by its very nature, rooted in protest. From blues and jazz through to soul, funk, disco and hip hop, the pioneering spirit of Black American music has been an urgent vehicle for expression when Black people’s voices were silenced in so many other oppressive ways.

The same goes for techno and the Afrofuturist meanings embedded in it. As a largely instrumental music, the message was often more subliminal or interpretive, but there were those – most notably Underground Resistance – who put Black politics front and centre. One of the other key proponents of unapologetically vocal, political techno is Eric Dulan, aka DJ Bone. Since the mid 90s the Detroit-born and raised DJ and producer has used his platform to shout loudly about the realities facing Black people in America, and specifically his home town. Across his early releases on his own Subject Detroit label, the message is loud and clear. It’s eerily prescient the first track on his label was centred on the mantra, “Black lives, poverty, aspiration.”

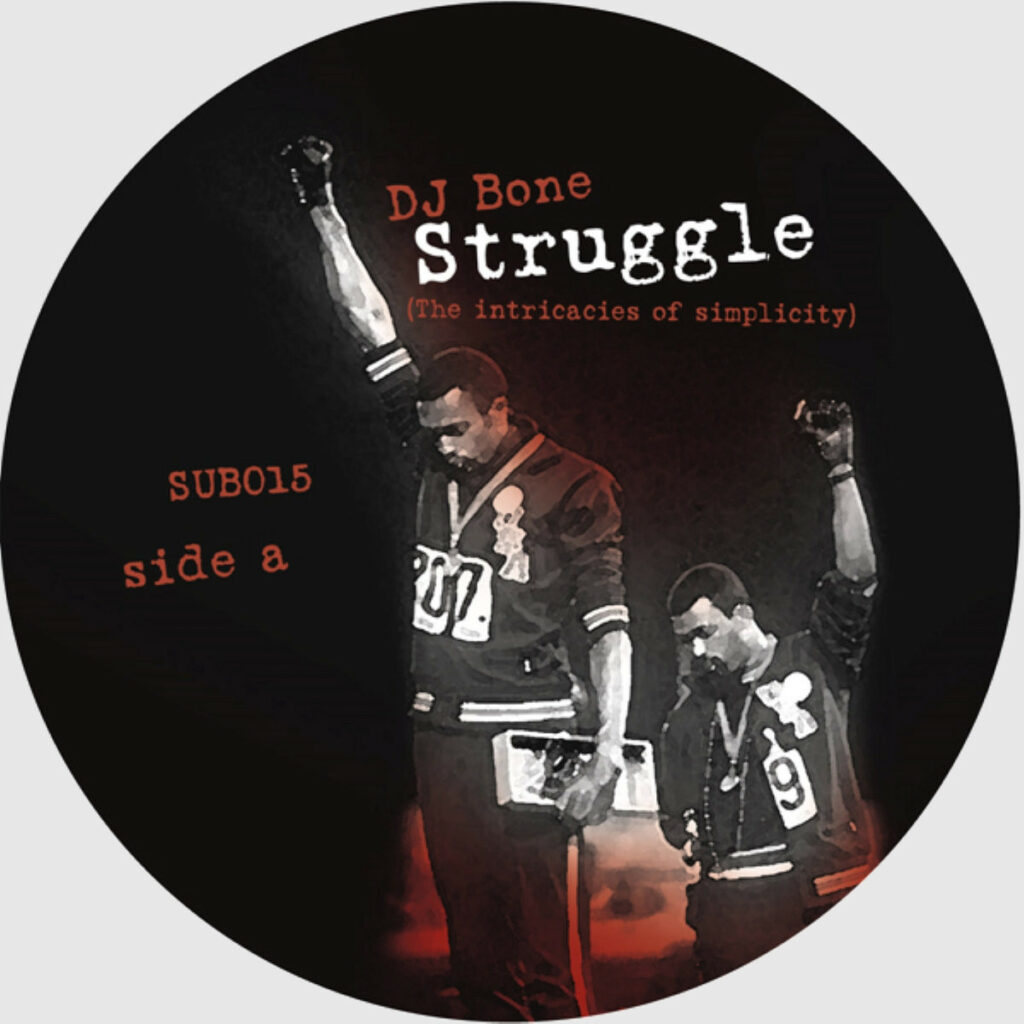

From honouring Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ iconic Black Panthers salute at the 1968 Olympic Games on the Struggle EP to unflinching explorations of the transatlantic slave experience on records like Ship Life, Dulan’s candour and provocation stood out in a genre that often preferred a certain degree of ambiguity. Having completed a production-oriented interview with Dulan just weeks before George Floyd’s murder, I felt it necessary to pick the conversation back up and examine his relationship with protest music in more detail. The following is a lightly edited transcript of the conversation, which took place over Skype between Bristol and Dulan’s current home in Amsterdam, the day after protesters were tear-gassed in front of the White House, when tensions in the US were at their peak.

Hi Eric, I hope you’re doing OK. It’s pretty crazy times we’re going through right now…

We’ve just been watching the US news non-stop, and every day it gets crazier and crazier. It’s nothing new, and of course Black people have been going through it in America for a long time, but this level of blatant harassment, aggression. I’ve never seen that since the civil rights movement.

Creative industries got behind this idea of muting their social media feeds for 24 hours as ‘Blackout Tuesday,’ but that doesn’t absolve the issue of racism in the music industry in general, and I was interested in what your experiences of that have been – things you think have been positive over the years as well as challenges you’ve had to deal with.

It’s bad enough they’re not booking enough Black artists. I just posted something the other day and it said, ‘Love Black people just as much as you love Black culture’ so to have a techno that’s born out of a Black city and to not to be represented on a global scale the way it should be… They don’t have to bow down and pay homage like crazy, but there should be some really prominent representation for Black people in this music, and the fact that we still push the boundaries should be on display as well.

Personally, I can’t say I’ve first hand run into someone who said, ‘I’m not booking you ‘cos you’re Black’ or something like that. But I just think that it’s harder. It’s harder for me to get the credit that I deserve. It’s harder for me to shine when there’s so much bullshit that’s being put out around me that doesn’t really deserve to be there. There’s so much crap out there that’s glorified, and it’s comical. I’m not saying that everything has to be serious. Look at [Detroit] Grand Pubahs. When they made ‘Sandwiches,’ it was comical, but it was creative as fuck and it was funky, the whole essence of it was genuine. It wasn’t something scripted and promoted to shit to make everyone say, ‘I guess it’s good because everyone’s talking about it.’

I think that’s the issue I have – they don’t want to find the talent, they want to manufacture someone into a star by saying, ‘oh this is the next big thing.’ Let the people decide that. Let the promoters book who they want to book, and then when the people go and see, they’ll know who’s good. It’s a lot easier for people who aren’t of colour and for guys to get up in there and be put on that pedestal, and that’s a shame.

If we consider it easier for white artists to get exposure and build a career out of a music that was pioneered by Black people, do you feel like appropriation is an issue?

Yeah. There’s appropriation there. I can’t even call it appropriation as much as it used to be, whether it’s someone paying homage or someone trying to copy. And it happened within the city, way before it even became a big thing outside of Detroit, with suburbanites and some other people. What you had was people trying to copy the essence of it and they couldn’t do it, so instead of saying, ‘Oh you got me, I can’t really copy that,’ they just took what they had and promoted the crap out of it so it worked, and people saw that formula and they followed suit.

Now a lot of the stuff coming out now, especially the EDM shit, I can’t even call that appropriation, ‘cos that’s nowhere near techno in my opinion, that’s a whole other animal. That’s like a derivative of really bad pop techno mixed with trance. I don’t even know what to call it, but I don’t hear techno in there, so that’s not appropriation to me. Instead they appropriated the culture of the travelling superstar DJ, which was pioneered by people like Jeff Mills. You had the house guys like Masters At Work. This image of being flashy and being the shit – these guys never had to act that way. Louie Vega’s the shit, period. Jeff is the shit. But it was because they were talented. They didn’t have to wave their hands around or do some kind of aerobics workout behind the decks. They just did their thing and they had that swagger that people liked, so they weren’t begging people to love the track they were playing. ‘I did my homework, and my job is to give you the best music possible in the funkiest way possible.’

Protest music is central to your back catalogue. Let’s talk about your relationship with protest music… where does it start for you in terms of the music you were growing up with?

It started really early. My parents introduced me to songs based on the message in the song. There was always something about it sonically that was appealing, but I would say 98 percent of the songs they ever played for me, they would sit there and explain the song to me. Like Gil Scott-Heron’s ‘Angel Dust’ – that’s how my dad would talk to me when I was really young about not doing drugs. Stevie Wonder’s ‘Village Ghetto Land’ talking about your environment, like, ‘What are you gonna do? That’s where you live and it’s not always meant to be looked at as a slum or a ghetto. That’s your playground, that’s where you’re growing up and where you’re gonna be hanging out.’ And things like Marvin Gaye, of course, Aretha Franklin…

Did it feel to you like this music was just a reflection of life, of the Black experience? A necessary community service, in a way?

It was political, and a lot of had to do with that, but then my dad would also play The Drifters’ ‘Up On The Roof’, from a reel-to-reel, and it’s just about getting away and having a place to clear your head, where you can just step out of things for a while and have a moment of peace.

But it did spill over into when I created music. It was natural for these songs to have a message. They have to express something. When I did ‘Black Lives’, that was it. Black lives, poverty, aspiration… That’s every day for me. Those three simple things. If you’re Black, you can’t hide it. And when you’re broke, you’re broke, but the aspiration… You’re always gonna want something. Whether you want to be better, or you want to do better. There’s always a hope. Most broke kids, that’s the one thing they all have in common – they all have hope. And that’s the thing you’ll always hear them say. ‘Man I can’t wait ‘til I can get out of the hood, or I can buy a car’. There’s always some kind of aspiration, but it was simple for me to put it in a song and then try and tailor the music to portray that mood.

The aspiration you talk about seems to tie into the idea of Afrofuturism, in what Drexciya were doing or even back to P-funk and so much of what Detroit techno was founded on – this yearning, this optimism for a better reality.

Drexciya spoke of the slaves that were either dumped off their ship or jumped off, and they were underwater breathers and had this whole existence underwater – a resistance that thrived and thrived. It goes hand in hand with Detroit. Even with Motown, there were a lot of political songs. There were happy, party songs, but there is a lot of political shit in there. You just have to catch it. It’s so funky you might not even know that they’re being political, but if you break it down…

So that carries over into when I do something like Ship Life, about slaves that would rather jump off a ship than be a slave. Those are choices. I hate when people say, ‘the struggle is real’ ‘cos they don’t understand the true meaning of that. You can’t say that because your favourite flavour of Fro-Yo isn’t available. The struggle is when you have to choose between slavery or death. The struggle is what’s going on right now in these streets. People protesting. That’s a struggle. A struggle is figuring out where you’re gonna get your next paycheque from and you’ve exhausted all options. People look down on all these dope boys out there selling dope – they don’t know if they’re trying to feed their family or whatever. The ends don’t always justify the means but you don’t know everybody’s story.

And there was a set of factors that set these things in motion in the first place, right?

Exactly. Lack of proper schooling, lack of nutrition. You name it. Clean drinking water. Space. If you’re cramped, living in the projects, you don’t see any greenery, you hear everyone’s noise, you smell everyone’ food, that’s like being in prison. The way it’s structured. And they structure up the freeways to make sure it’s not gonna be an eyesore, or not have people able to flood into a certain other area of the city. It’s seclusion.

Which make the hopes and aspirations that can survive in that situation all the more incredible.

That’s the beauty of the essence of Black people. I was raised to understand that I had to be three times as good just to be considered equal to any white person. Not that I was a third of a person, but just that society was gonna come down on me so hard as a rule that I would have to over achieve just to be equal. So I carry that same burden when I go behind the decks. That’s why I’m serious. That’s why I’m not up there to be court jester or some mime conducting an imaginary symphony on a CDJ, ‘cos this is serious for me. I had to work hard to get to where I am, and I have to work even harder to be respected.

There are so many amazing people that don’t get to see the light of day behind the decks on a global basis, so every time I’m up there I don’t feel like it’s just me. I’m representing all these people who deserve a chance or never got a chance. So I’ve gotta actually crush that shit, I have to tear the roof off. In essence, all that’s doing is make me look equal to some of these people who push a button, dance around for four minutes and do another quick mix. Theatrics. I’m not against it, but it’s not fair that I have to put in so much work to be considered equal to some clown shit.

It’s telling that when I think of a DJ miming and posing behind the decks, it’s invariably a white DJ like David Guetta that I picture…

Did you see that bullshit he did recently? Where he played that Martin Luther King speech? And then had a drop? I was like, ‘What the fuck is wrong with him?’ I understand pop music, publicity, marketing, promotion, but come on now. At this time, for this situation, he’s the one? That tune? Really? Can I at least get Carl Cox up in that motherfucker? He’s my man.

Carl Cox may be well entrenched in ‘the machine’ as it were, but he’s always real.

He participates in the commercial aspect, but I have the utmost respect for Carl. He would ask me to come and play Ultimate B.A.S.E. personally. Whenever Carl would come to the D, it would be a big deal because not many people that come to the D are liked. There were very few people where, if they came to the city, they could hold court and say, ‘I wanna have a meal’ and everyone would show up. Even people who didn’t like each other would show up and break bread and kick it. Laurent Garnier is one of those people. Dimitri Kneppers from Amsterdam. Carl Cox is another one. He comes to Detroit and I got Mad Mike calling me on the phone, which is huge enough, but he’s like, ‘Yeah man we’re at the restaurant getting some Arabic food, and Carl Cox is like where’s Bone? Are you on your way? Cos he keeps bugging us.’ And we had a good talk. He told me, ‘I’m the people’s DJ. I never claimed to be the king of the underground. I’m here for the people, and whatever they want me to play, I’m going to play it. That’s what I’m all about.’ And I was like, ‘yeah, I respect that.’

And he can play. I might not always love what he plays, but I’ve heard him play an all Detroit set before, and I’ve heard him play at Ultimate B.A.S.E., and he’s no joke. He’s a great DJ. But yeah, could we at least have gotten Carl up on top of that roof?

Bringing it back to some of your specifically politicised tracks, where does the speech in ‘Cause Of Action’ come from? I was trying to search for it to work out the source…

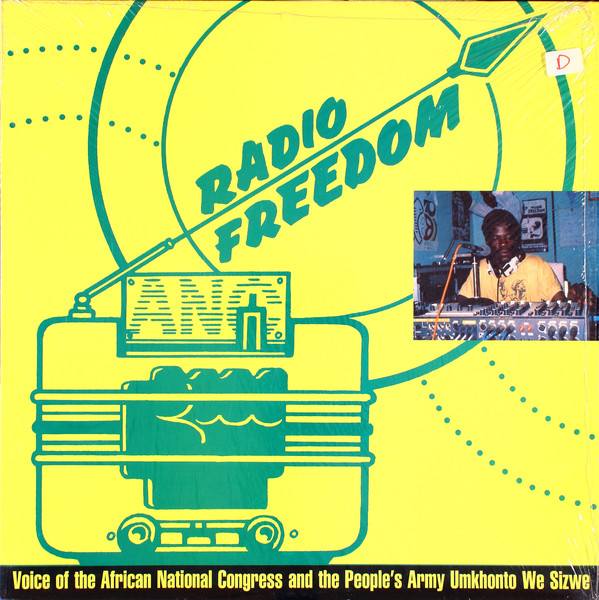

Oh, you won’t find it brah! It’s from an old broadcast they had in South Africa called Radio Freedom. They were there to oppose Apartheid, to get the message to the people and to organise, and it’s a powerful thing to listen to. I found a couple of them on vinyl, and I would just listen to them non-stop. That’s where you hear passion and purpose in people’s voices. I had speeches on vinyl from Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr, Nelson Mandela, you name it.

To me, the vocals I got for ‘Activist’, which says, “activist, revolutionary,” are powerful. Just having someone say those two words, where it echoes out over and over and over. That’s why the music was that way. It was driven, like what you’re seeing now with the protests, like a march.

It’s very much the same with the vocal in ‘It’s Over’ – “Strong! Upright! Sober! Together! Unity! Justice! Freedom!” It hits home because you kept it direct.

Man… I’mma have to start shipping out some of these digital downloads to protestors like, ‘Here, I had your soundtrack about 10, 15 years ago!’

Beyond the stuff you grew up with, what other Black protest music has been important to you through the decades? We haven’t touched on hip hop, and there’s obviously so much embedded in there, not least with a crew so specifically direct in their message like Public Enemy.

Ohhhh man.

How important are they to you?

Huge. Honestly, my favourite hip hop group of all time is Public Enemy. I have every single album, every single release, you name it. Put it this way – I’m as big of a Public Enemy fan as Moodymann is a Prince fan. And it’s the militant message they had, but to me it wasn’t militant, it was just common sense. Even when Flava Flav was being comical and he said, ‘911 is a joke,’ it was serious to me.

When I was a young adult and I came back from playing basketball at the park, my friends dropped me off and I go in the house, my dad wasn’t home, and the house had been broken into. I’m walking in thinking, ‘what if they’re still in my house?’ I had a gun in the house, but how am I gonna go and try and get this if somebody’s still in there? So I go to the neighbours, I call my friend that just dropped me off. He comes back over with his gun, and then we clear the house, make sure nobody’s there, and then we call the cops. And the cops ask, ‘so are the robbers still there?’ ‘No’. And they said, ‘well in that case we’re not gonna send anybody out. You just have to go to the police station and file a report.’ So when Flav said 911 is a joke, I heard him. It wasn’t a controversial statement for me!

And as much as Flav was dressed up as a figure of fun at that point, the message was still on point.

‘Black Steel In The Hour of Chaos’, all this stuff. X Clan, Dead Prez – what I loved about these groups is unlike other people who floated in and out of the politics of what it is to be Black, I just liked the guys who were always in it. There was this one rapper called Paris who followed the beliefs of the Black Panthers, and a lot of what he said is 100 per cent true right now. It was 100 per cent correct when everybody said NWA were the ghetto CNN. They were reporting what they were seeing every day in the hood. Now look at everybody saying, ‘Fuck the police.’

That tune alone is just enshrined in modern culture. It’s part of our vocabulary.

And they caught hell for it back in the day. They got banned and they got arrested and followed, you name it. So I was influenced by a lot of that. Even the stuff that wasn’t militant, whether it be De La Soul or A Tribe Called Quest, that was more on a conscious tip of being proud of who you are as a Black person. That too resonated with me because it was difficult.

At the time I’m growing up, I don’t see Black people in the TV shows I’m watching. I see Dukes of Hazzard with a fucking confederate flag on top of the car. I see the Love Boat, with one Black person, one! There’s no Black people on Fantasy Island. So every show you might get one Black person, every movie you might get one Black person, so it gets to this point where you’re either desensitized to it and you accept it, or you go, ‘man, fuck this, where’s the Black shit? And you look for it.

Was anything else you thought we should cover in relation to your music as protest music?

I can’t really say. Just the fact that I have been doing it – ‘True Warriors’, ‘Activist’, ‘It’s Over’, Ship Life EP, ‘Black Lives’, it’s been me and I’ve always been true to myself.

When people around the world now are waking up and going, ‘I’m shocked and appalled that they’re treating people this way.’ You shouldn’t be shocked. You just decided not to pay attention.

Editors note: The fee for this article has been donated equally to Blueprint for All (formerly the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust) and Project Zazi, part of OTR Bristol.